A Paston Introduction

A replica Paston Letter, penknife and seal - Norwich Medieval SocietyThrough the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries the Paston family amassed a remarkable private archive of some 2,000 letters, documents and a cornucopia of bits and pieces. During the medieval period, the Pastons rose from being bondsmen in a small village in north Norfolk to being great landowners, one of the four greatest landowners in Norfolk and in Tudor times courtiers at the court of King Henry VIII. In the era of the Stuarts their fortunes faded away.

A replica Paston Letter, penknife and seal - Norwich Medieval SocietyThrough the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries the Paston family amassed a remarkable private archive of some 2,000 letters, documents and a cornucopia of bits and pieces. During the medieval period, the Pastons rose from being bondsmen in a small village in north Norfolk to being great landowners, one of the four greatest landowners in Norfolk and in Tudor times courtiers at the court of King Henry VIII. In the era of the Stuarts their fortunes faded away.

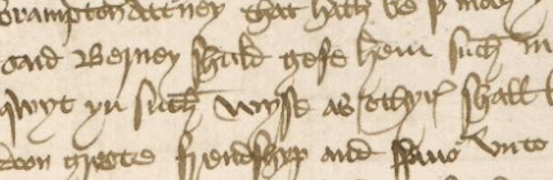

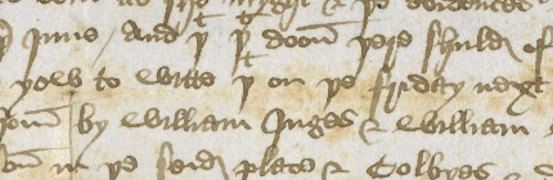

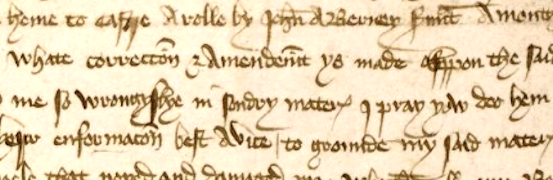

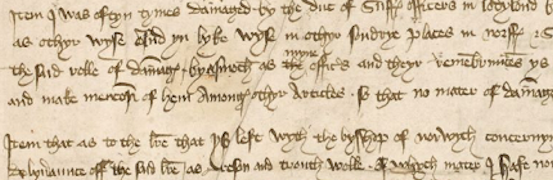

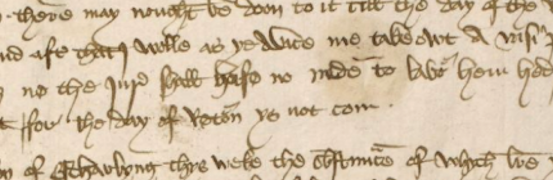

The Paston Letters and papers are frequently taken to date from 1418 until 1509, and indeed this is the period for which they are most often used as a resource when studying social history, English medieval literature, paper-making or even watermarks. However in total, they run right through to the demise of the family at the end of the 17th century. It is thought they were all together at the time they were discovered in the muniment room at Oxnead Hall in the 18th century, but gradually became dispersed. This web site seeks to draw together those various letters into one place, as a source to investigate the rise and fall of one remarkable family.

The Early Pastons

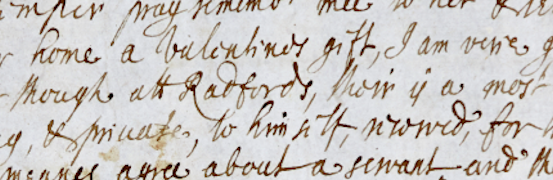

Through their medieval correspondence, we build a picture of the main Paston family characters: the wily Judge William and his daughter-in-law, the redoubtable and courageous Margaret, defender of the family estates. We encounter her husband John I, sons John II and John III, and the members of the family household. We share in the repercussions of Fastolf's disputed will and the drama of a family scandal surrounding a controversial marriage, and we read the first ever Valentine letter in English.

One of the last of this sequence of letters, in 1500, contains an instruction from Henry VII to attend the marriage of Arthur and Katherine of Aragon. Another document of 1506 has a description of the grand meeting, which much splendour, of Henry VII with Philip, King of Castile at Windsor after Philip's ship was driven ashore on the English cost.

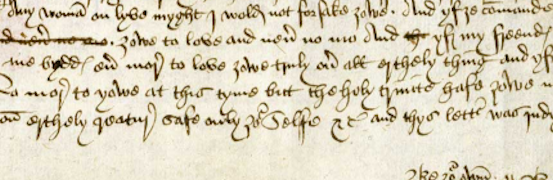

The Paston family were also unique in their time by living right through one of the worst civil wars in this country, the Wars of the Roses, and coming out not only unscathed but richer. The Paston family fought for the Lancastrians at the Battle of Barnet in 1471. John Paston III also fought for Henry VII at the Battle of Stoke in 1487.

In the siege of Caister Castle we have the only battle of the Wars of the Roses to take place on Norfolk soil: it was an attempt by the Duke of Norfolk to retain the castle, which he claimed Sir John Fastolf had given to him, rather than to the lowly lawyer John Paston.

Thomas Paston, as a gentleman of the bedchamber for Henry VIII, served in a difficult and distasteful personal role to the king, but this is what gave him his later great estates in Norfolk, particularly at Binham Priory, Blofield and Thorpe St Andrew.

Seafarer Clement PastonClement Paston, who died without issue at Oxnead, served under four of the Tudor monarchs. He left his considerable estates to both the elder half of the family, the descendants of his brother Erasmus and to Edward Paston, the descendant of Thomas Paston, the younger brother. It was not an easy settlement and this led to some of the later letters between Edward Paston and his cousin's wife, Katherine Paston, who was living at Paston Hall at the time, the last of the family to do so.

The house at Oxnead was left to his nephew Sir William, making him one of the richest men in Norfolk. He was known for his liberality and generosity; Sir William would found the Paston School at North Walsham.

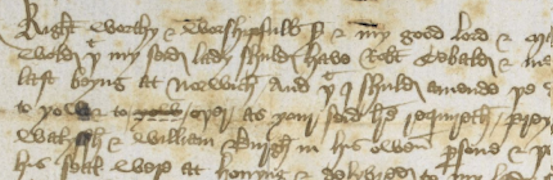

The Lady Katherine letters

These relatively unknown letters deal partly with the Paston estate, because Katherine's husband Edmund was unable to deal with these matters himself, and partly and most poignantly with her son's welfare. The letters are now in the British Library; they were published in 1942 by the Norfolk Record Society.

Katherine's son William was away at Cambridge (and of course people went to Cambridge colleges much younger then than they do now). She attempts to 'feed him up', sending him turkey pies in Lent when she shouldn't have, and to stop him from becoming too sweaty from 'tennising', as she is sure that playing tennis is a wicked and overly active sport that will lead to humours in the brain. She also relates how the village of Paston itself is decimated by the plague, not once, but twice, with the Pastons transferring to their other home in Palgrave. This again was quite common at the time. For rich families, one of the greatest bounties was that they were able to move away from a village when plague came calling and to move on to one of their other great houses. This was not the case with the poor, who had to sit it out.

A Whirlpool of Misadventure

The wonderful collection of letters relating to Robert Paston were published in 2012 by the Norfolk Record Society with the title 'A Whirlpool of Misadventure' . These letters reveal his hobby of alchemy, his great love for his wife, his estates, his awareness that his control of the estates is failing and that the Pastons are headed for bankruptcy, and his great sadness as one after another of his children dies.

In this period Robert probably commissioned the painting The Paston Treasure. It has a worldwide audience, it is the Castle Museum's most requested item for loan, and their associated workshop for local schoolchildren is their most heavily subscribed schools activity. What our project unveils is how the letters shed light on the painting and on the life and career of William Paston (1610-1663), the traveller and collector and his uncle Edward Paston who lived in Blofield a keen musician and patron of Tallis and Byrd. You can explore the painting in interactive ways on the Oxnead page.

The Paston Letters end with the death of the Second Earl of Yarmouth in 1732 with no male issue, as his three sons had died before him. (His daughters were still alive, but they didn't count in the succession.) He died more or less bankrupt, and his estates were sold up, most notably that at Oxnead.

The Saga of the Letters

Sir John Fenn, Fenn's Paston Letters, Vol. VWilliam Paston, 2nd Earl of Yarmouth, had sold some of the Paston Letters to the great antiquarian Peter Le Neve before his death, and some became part of the collection of the historian the Rev Francis Blomefield. From there a large proportion of the letters made their way by circuitous routes to 'honest' Tom Martin, who also died bankrupt, and from there through Worth, a chemist in Dereham, to John Fenn, who at last saw the value of the letters to our understanding of history and transcribed them most carefully, presenting them to the public in two volumes in 1767. The letters were immediately a great success. They sold out in a week and John Fenn was knighted, as he had always hoped to be when he dedicated the letters to the King. From that time to this the Paston Letters have never been out of print, and their story has included their loss, their recovery, declarations in court that Fenn was a liar and declarations in court that Fenn was not a liar, and that the letters were genuine. All this because the letters are unique, not only in English history but throughout Europe, in showing through three centuries the rise and fall of one great family.

Sir John Fenn, Fenn's Paston Letters, Vol. VWilliam Paston, 2nd Earl of Yarmouth, had sold some of the Paston Letters to the great antiquarian Peter Le Neve before his death, and some became part of the collection of the historian the Rev Francis Blomefield. From there a large proportion of the letters made their way by circuitous routes to 'honest' Tom Martin, who also died bankrupt, and from there through Worth, a chemist in Dereham, to John Fenn, who at last saw the value of the letters to our understanding of history and transcribed them most carefully, presenting them to the public in two volumes in 1767. The letters were immediately a great success. They sold out in a week and John Fenn was knighted, as he had always hoped to be when he dedicated the letters to the King. From that time to this the Paston Letters have never been out of print, and their story has included their loss, their recovery, declarations in court that Fenn was a liar and declarations in court that Fenn was not a liar, and that the letters were genuine. All this because the letters are unique, not only in English history but throughout Europe, in showing through three centuries the rise and fall of one great family.

So in the Paston Letters we have treasure not only for historians but for linguists, genealogists, writers and landscape archaeologists of all ages. But to a large extent this treasure is still hidden.

We are linking the people in the letters to the places were they lived. The work of interpretation has been hampered not only by the language of the letters, which required transcription so that Fenn's public could understand it even in 1787, but also the difficulty of research, since so many of the letters are in the British Library in London or in the Norfolk Record Office.

These bodies have been digitising the letters for the first time and, with the help of a wealth of talent in local research that branches in many directions, we hope to interpret this treasure in such a way that the letters may delight a new audience, just as they delighted the public in 1787.

We hope that you will be inspired to join in some of the further online events we are holding in the coming months. Even if you are not able to come to Norfolk in person, do join in via our online community. We look forward to hearing from you.