The Village of Gresham and the Pastons

In spite of a number of additions and alterations in later centuries, the parish church at Gresham would be recognisable to the medieval Pastons.In 1426 Judge William Paston began his ambitious investment in land in the wealthy Hundred of North Erpingham with the purchase of the port of Cromer. The acquisition of Gresham followed in 1427. In the 1440s the disputed estate of East Beckham was finally secured and, through the marriage of his eldest son to Margaret Mautby, the adjacent estates of West Beckham and Matlaske. The area provided excellent grazing and fertile soils, with fast-running becks to drive the mills. Cromer and Blakeney provided the trading outlets. This area became one of the key sources of income and influence for the Paston enterprise.

In spite of a number of additions and alterations in later centuries, the parish church at Gresham would be recognisable to the medieval Pastons.In 1426 Judge William Paston began his ambitious investment in land in the wealthy Hundred of North Erpingham with the purchase of the port of Cromer. The acquisition of Gresham followed in 1427. In the 1440s the disputed estate of East Beckham was finally secured and, through the marriage of his eldest son to Margaret Mautby, the adjacent estates of West Beckham and Matlaske. The area provided excellent grazing and fertile soils, with fast-running becks to drive the mills. Cromer and Blakeney provided the trading outlets. This area became one of the key sources of income and influence for the Paston enterprise.

Gresham's importance as a settlement had earlier been recognised by the building of fortifications, with the most substantial fortified structure built in 1319 by Sir Edmund Bacon.

Ownership disputed

Judge William Paston gave the Castle to John and Margaret. In 1444 the Judge died, and the young John and Margaret were left to defend his legacy. The Judge had also left them his agent in the area, James Gresham (the Gresham family were destined to enjoy similar financial success to the Pastons).

Shortly after the death of the Judge, the family's enemies moved to dispute the ownership of Gresham, which the Judge had purchased from the joint owners, Thomas Chaucer (grandson of the poet) and Sir William Moleyns. After Chaucer's death, his daughter Alice married into the De La Pole family, later to succeed as the Dukes of Suffolk and to become implacable enemies of the Paston family.

Campaign of intimidation

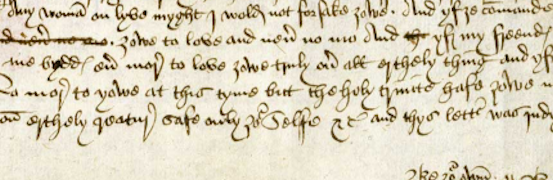

The first metre of the walls and towers and the moat of Gresham Castle are hidden today by low vegetation and trees.Lord Moleyns, aided and abetted by John Heydon of nearby Baconsthorpe – a bitter local rival of the Paston family – lodged a claim on Gresham and launched a campaign of intimidation and threats to the Pastons' tenants. Margaret Paston's letters to her husband John, now fighting their cause in the London courts, provide from this time some of the most famous and vivid passages of all the Paston Letters.

The first metre of the walls and towers and the moat of Gresham Castle are hidden today by low vegetation and trees.Lord Moleyns, aided and abetted by John Heydon of nearby Baconsthorpe – a bitter local rival of the Paston family – lodged a claim on Gresham and launched a campaign of intimidation and threats to the Pastons' tenants. Margaret Paston's letters to her husband John, now fighting their cause in the London courts, provide from this time some of the most famous and vivid passages of all the Paston Letters.

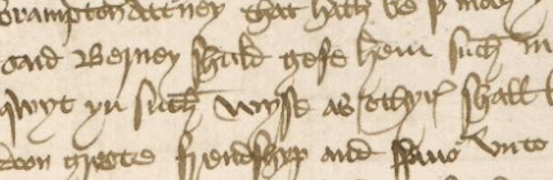

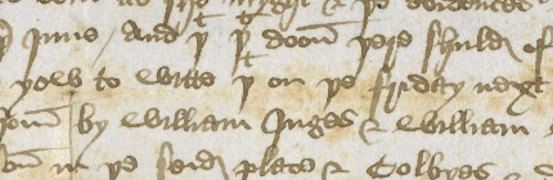

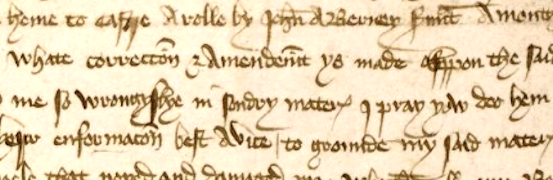

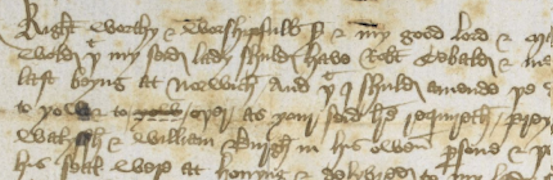

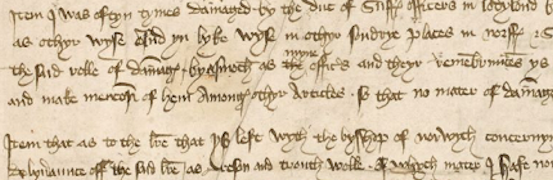

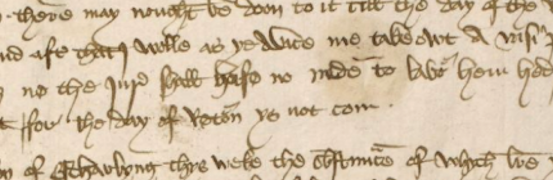

In one letter Margaret describes how, in 1448, Moleyns' army of perhaps several hundred finally ejected the Paston household from the Castle, forcing her to write to her husband asking for supplies with which to defend their other houses in the area...

and ask you to get some crossbows, and windlasses to wind them with, and crossbow bolts, for your houses here are so low that no one can shoot out of them with a longbow, however much we needed to. I expect you can get such things from Sir John Fastolf if you were to send to him. And I would also like you to get two or three short pole-axes to keep indoors, and as many leather jackets, if you can.

Pupils from Gresham school meet Margaret Paston and one of her retainers at the castle, to hear how she was thrown out.Loopholes at every corner

Pupils from Gresham school meet Margaret Paston and one of her retainers at the castle, to hear how she was thrown out.Loopholes at every corner

Partridge [the bailiff of Lord Moleyns, with whom the Pastons were disputing] and his companions are very much afraid that you will try to reclaim possession from them, and have made great defences within the house [the castle], so I am told. They have made bars to bar the doors crosswise, and loopholes at every corner of the house out of which to shoot, both with bows and handguns; and the holes that have been made for hand-guns are barely knee high from the floor; and five such holes have been made. No one could shoot out from them with hand bows.. . .

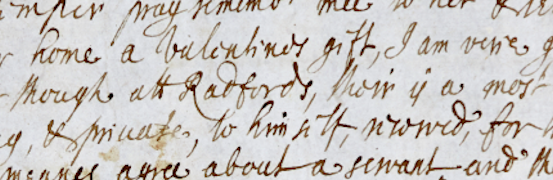

and, in the same letter, showing characteristic courage and self-possession by including other items of importance…

Please be so kind as to buy me a pound of almonds, a pound of sugar, and buy some frieze-cloth to make gowns for your children. You will get the cheapest and the best choice from Hay's wife, I am told.

Duke of Suffolk executed

Margaret was forced to flee to family friend John Damme's house, a mile away at Sustead.

In 1450, the then Duke of Suffolk was executed and much of the Duke's protection for the lawless activities of the likes of Moleyns and Heydon disappeared. John Paston was able to recover Gresham Castle. The Castle was never rebuilt, despite an idea for reconstruction apparently being considered in the 1470s.

Gresham remained an important foundation for the Pastons' success in the Tudor period. The cluster of estates in the area, which by now included Barningham and Bessingham, was the location for the building of the magnificent Barningham Hall. The hall, now in private ownership, was built by Edward Paston in 1612 and is the only surviving Paston property.

You can see the Footprints rebuilding of Gresham Castle.